River Banksy (2017)

By

Adrian Barron & Shelagh McCarthy

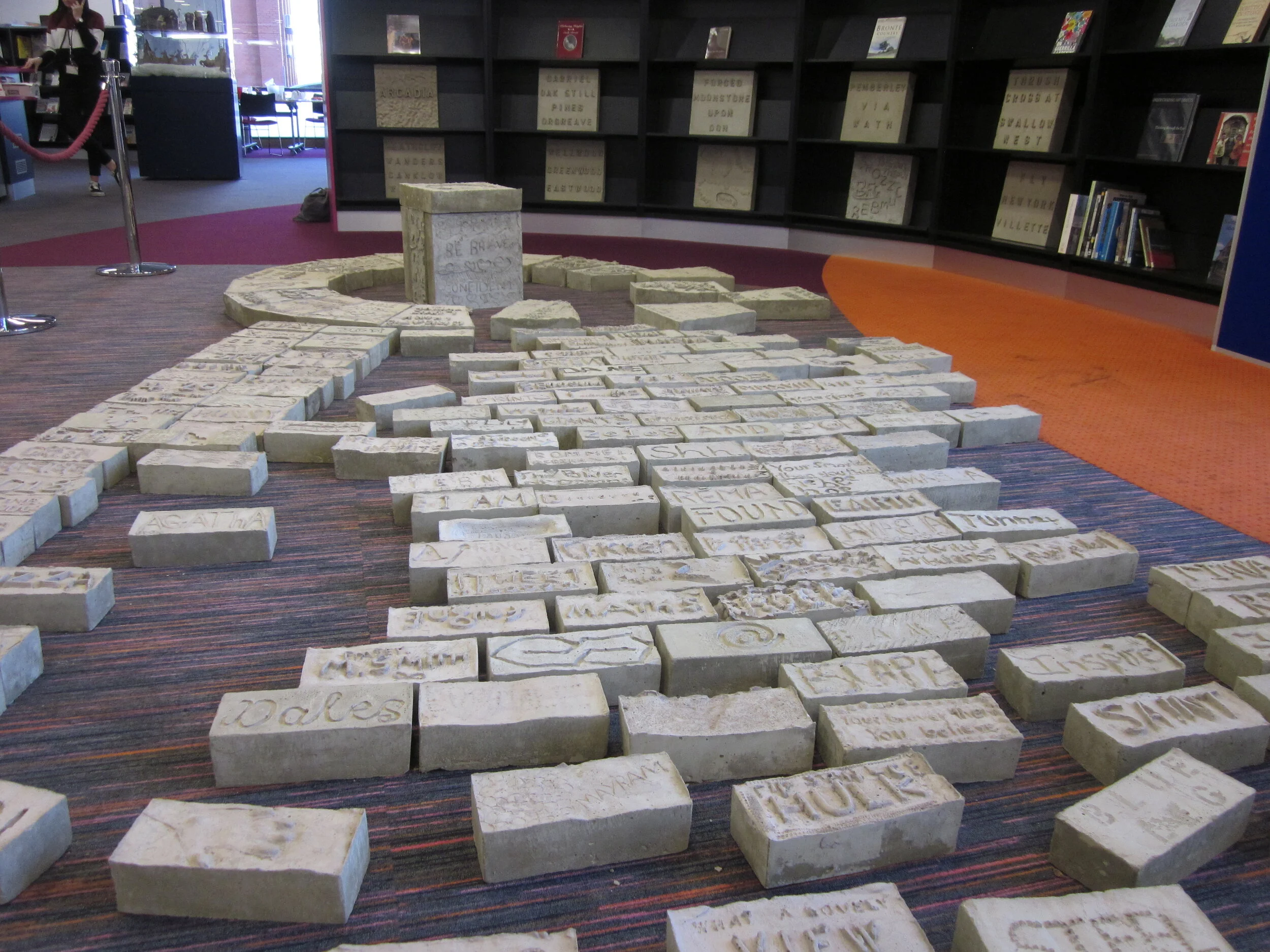

A photograph showing a series of customised ‘bricks’ displayed in the entrance to a public library.

The initial brief called for ‘creative and disruptive activities’ in a library, and ‘to demonstrate and encourage risk taking... offering activities that are unexpected and surprising’. We proposed and created, A Garden in Rotherham Riverside Library.

In a letter to his friend Varro, Cicero, the Roman statesman and philosopher, wrote, “If you have a garden in your library everything will be complete.” (46 B.C.) Gardens, like libraries, are transformative spaces - spaces for creating, growing, thinking, communicating, learning, dreaming. Public gardens, like public libraries, are democratic spaces with open access to all manner of information and discussion, and can provide cultural and creative opportunities that enrich lives. Both are important in developing local quality of life, sense of place and society, and individual wellbeing. They support social cohesion, build skills and reduce social isolation by encouraging participation in shared activities (Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Libraries Deliver: Ambition for Public Libraries in England 2016 to 2021).

Significantly, gardens and libraries (and the books and information that fill their shelves) can also be subversive spaces. Our garden is a physical installation of sculptural forms cast in cement that refer to both actual and narrative gardens. It is both memorial and anticipatory - a memorial in part for the books of words that record ideas that have been lost through time as a result of natural and manmade causes, and an anticipation of new narratives and ways of thinking that are yet to be created.

This installation of physical cement poetry has been made by residents of Rotherham who attended workshops run inside the library during the month of October. We supplied the concept, materials, working methods and produced a few of the blocks, our participants created the rest. We hope that our work in Rotherham Riverside Library will continue to inspire similar undertakings by subsequent artists working within libraries. We hope that the ethos embedded in our work and the text blocks themselves, survive.

Together we led 6 consecutive drop-in day workshops during the October half term. For the majority of the week, we were assisted by Manesh, an artist mentee recruited by ROAR, the innovative, Arts Council funded multimedia arts organisation based in Rotherham, through whom we’d been commissioned. After I left for work commitments in London, Adrian delivered 3 further workshops with specific groups booked by the library. I joined Adrian again for the final 2 days of installing and for the opening of the show of work. The project was aimed at young adults aged 12 -25, and Riverside Library librarians. Reflecting the reality of young people’s lives, library users, family groups and childcare responsibilities during school holidays, our actual participants ranged in age from 5 - 60. Over the course of the project 100+ participants were engaged. This includes the general public, targeted school groups and 10 librarians. Specific target audience engaged = 70 Languages spoken and recorded = ? The studio space comprised 2 areas: a peaceful space containing an unrolled 10 meter roll of paper covering the floor, where words, languages, marks and ideas could be played with, printed, written, arranged, practiced and where names and greetings could be left - a gentle, accessible way into the project - and a larger hands-on construction site where the cement was mixed and the bricks were produced.

We were keen that all participants would find something both familiar and unfamiliar to engage them. Many were new to the library and were surprised by the range of resources that could be found. Discovering a busy working art studio in the heart of a library challenged many of their library preconceptions and delighted them. It became increasingly evident that it challenged, though not wholly delighted, library workers too. The participants were keen to share skills and languages, engage in the processes, learn techniques, discuss ideas about the concept of the project, its production, its methods, and the materials and tools used. What we had not considered in our original proposal, but have subsequently been drawn to explore, is the migratory aspect of gardens. Like ideas, plants can be manipulated but not bounded by human intervention; they grow where they find favourable conditions. Whilst making, the participants would verbally discuss their own experiences of gardening and construction, and significantly, of migration. They wondered what would happen to the work. They wondered when we or other artists would come again. By then end of the project 175-180 bricks were produced, 152 standard bricks by participants, the larger pieces were made in collaboration or by the lead artists. The final two days were devoted to installing the work. An exhibition area at the entrance of the building was selected by the library administrators after a great deal of negotiations and discussions with a range of stakeholders in the space. It was this stage of the project that we felt the purpose of our work and our role as artists became compromised. Authorship and curatorial decisions regarding the way the work was presented created tensions between the artists and the library staff. Primarily this was the result of different expectations and lack of understanding from both sides, from the library and building staff about the creative process and the role of the lead artists and from the artists and commissioners regarding issues around the public space and other tensions facing public staff with external situations.

Passions ran high and compromises were made all round, and the resulting installation is a triumph and something to be proud of. The project exceeded all targets and expectations. What remains is to ensure the legacy of the hard work from all involved continues. To this end a web site is being developed to capture the excitement and engagement of the participants and the journey travelled to create this disruptive and provocative concrete garden. One unexpected outcome is the possibility of the words chosen for the bricks being translated into a choral piece for the improvising choir, Juxtavoices which can be performed in the same space at a later time. The project has also generated further interest from a London based school who have contacted the artists to explore a similar project for their external space, demonstrating the value of skills based creative activity as a means to excite and engage.